OFF-grid

Richard

Chivers

Celebrating gasholders

Photographer Richard Chivers has spent eight years capturing iconic gas holder structures around the UK, documenting them before the majority disappear forever.

Since then he has visited 50 around the country.

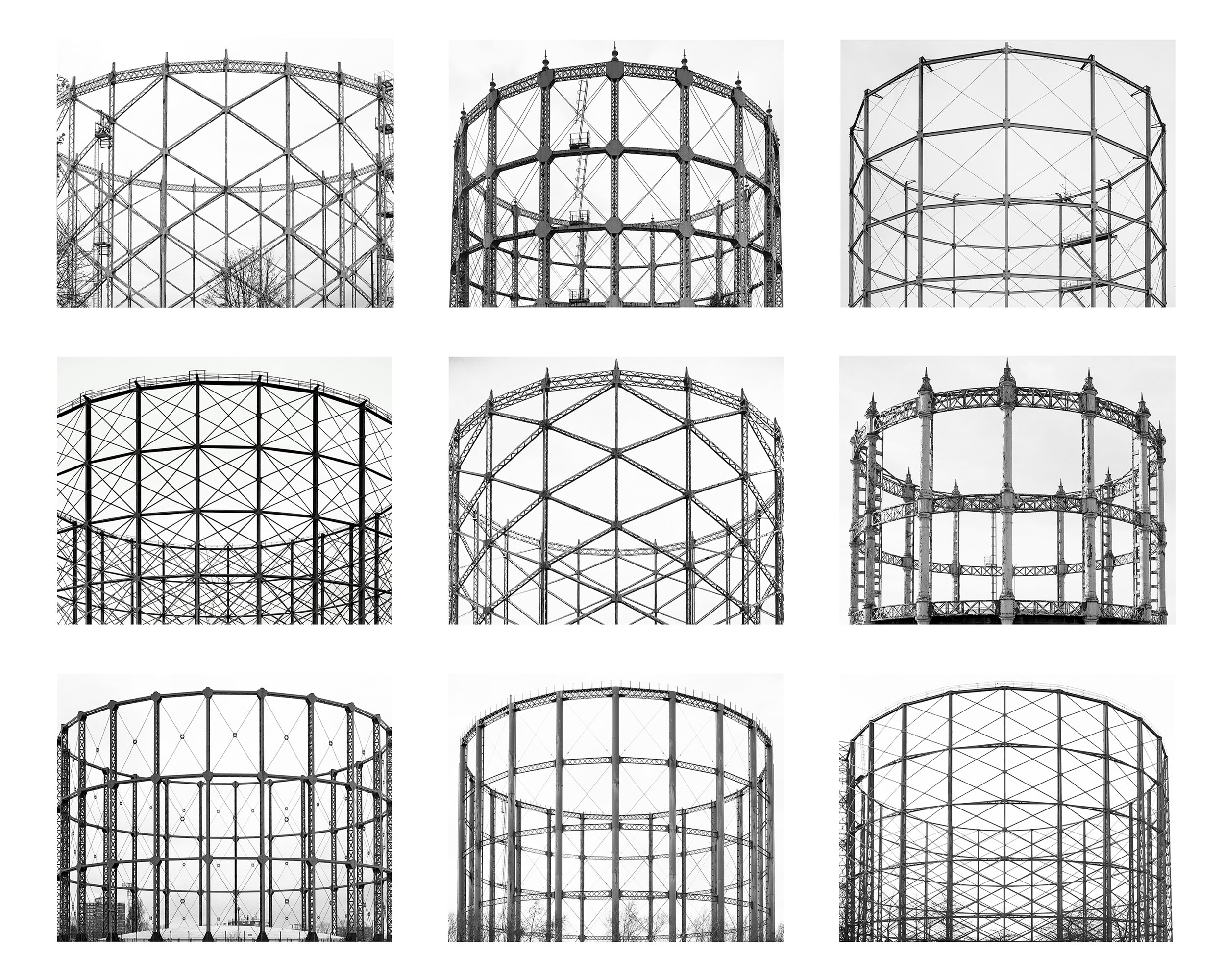

The exhibition featured a mix of colour and monochrome images. When visiting each site, Chivers would capture wider contextual shots in colour, and then produce tightly-composed detailed photographs in black and white.

Portrait: Paul Walsh

About the artist

Richard Chivers is a documentary photographer based in Brighton UK. His work generally focuses on the shaping and re-shaping of the British landscape, with a particular interest in the passing of time and capturing history and memory within the landscape.

Richard has exhibited across the UK and internationally including Format International Festival, Cannes Festival and the Brighton Photo Fringe and Biennial.

His work has been published in various places including the Observer, Guardian, New York Times, Source magazine, British Journal of Photography, and Dezeen. Publications include 'Passing Time (Brighton)' by Another Place Press, 'OFF-Grid' by Stanley James Press and 'Textures of Time' by Chalet Alpen. He is also a member of the Map 6 Collective whose recent work includes projects in Milton Keynes, The Shetland Islands, Finland and Wales. Their publication ‘Wales: The Landscape project’ was launched in April 2023.

Further reading

-

Gasholders have been a distinctive feature of the urban landscape since Victorian times.

They were the most prominent landmarks of Britain’s gasworks which brought light and warmth to people’s homes. As enormous skyline structures, gasholders have been both contentious and evocative, loved or loathed by sections of society. In recent decades hundreds have been demolished and lost from the landscape forever.Gas lighting was pioneered in Britain towards the end of the 18th century and the world’s first public gasworks built at Westminster in 1813, long before electricity. Gas was made by burning coal in ovens called ‘retorts’. However, once it was produced ‘coal gas’ needed somewhere to be stored: a gasholder – sometimes also, erroneously, known as a ‘gasometer’. These dramatic structures sprang up across the country. The typical form comprised a circular metal frame supporting a telescopic gas vessel, which rose, as it was filled, and fell, as it was emptied, within a circular water-filled tank set in the ground.

Gasholders revolutionised structural engineering. Initially, most frames were built of classical-styled cast-iron columns linked by girders. However, they soon began to make use of new materials and structural forms. The famous gasholder next to the Oval Cricket Ground, Kennington, was an early such use of wrought-iron, whilst the gasholder at Old Kent Road, Southwark, was built as a thin cylindrical ‘lattice shell’, inspiring the development of geodesic structures; a form seen in the Wellington Bomber airframe.

Gasholders were also a signifier of our industrial and working history, including the formation of trade unions, company profit-sharing, and, for a time, nationalised utilities. Many were located amidst working class communities; the waste from the Beckton Gasworks were famously known as the ‘Beckton Alps’, providing a toxic playground for children.

They could also be cultural icons, with gasholders appearing in photography, film, music videos and poetry. Their stark functional beauty inspired the German photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher who presented multiple images of gasholders, taken from the same distance and angle, in a grid or ‘typology’ to emphasise the uniformity of their design. The Bechers’ images of European industrial buildings became one of the touchstones of contemporary landscape photography.

The King’s Cross gasholders famously appeared as a backdrop to a robbery scene in the 1955 comedy film ‘The Ladykillers’, while a now-demolished Greenwich gasholder appeared in the music video to Blur’s hit single ‘Parklife’. More widely, Beckton Gasworks appeared in Stanley Kubrick’s film ‘Full Metal Jacket’, James Bond ‘For Your Eyes Only’, the film adaptation of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, and the music video for the Oasis hit single ‘D‘You Know What I Mean?’.

In the late 20th century, natural gas replaced manufactured coal gas. It could be transported from the North Sea and stored in pipelines, making gasholders redundant. A few found new uses, surrounding apartment blocks at King’s Cross and, soon also, at Bethnal Green and Kennington – therefore, having an important role in placemaking. However, most others have been torn down leaving some feeling nostalgia for the loss of these architectural and engineering marvels, something lucidly summed up in an extract from the poem ‘Gasometer’ by Scottish Poet Laureate Edwin Morgan:

‘You don’t care about the wildness of the sky, my old gasometer! …I have seen your stark ring taking sunlight till you were something molten, vanishing, magical…

Day of tearing down, day of recycling, wait a while! Let the wind whistle through those defenceless arms and the moon bend a modicum of its glamorous light upon you, my familiar, my stranded hulk – a while!’

Sebastian Fry is an archaeologist and historic buildings specialist who works at Historic England.

-

Since the Victorian era, circular gas holders became commonplace industrial icons on our urban skylines.

The design of vast telescoping tanks to store coal (town) gas was at the vanguard of civil engineering. They represented a modernising Britain, and for three decades after World War II were visible icons of our nationalised utilities, metal symbols for a vital infrastructure held in common for the public good.In 1965, North Sea natural gas was discovered. The UK supply network was converted from coal gas, and gas holders were only required for additional storage. As network capacity grew, gas holder utilisation dwindled.

By the 1990s they were redundant; widespread dismantling of the metal giants began in 2000.

Many have distinctive and intricate designs, each slightly different. Although defunct, those remaining continue to act as prominent landmarks, provoking a debate about their preservation and reuse. They are a reminder of our industrial heritage, a communal architectural experience that provokes awe in a way that few other structures inspire.

Inspiration for the project came from two places. ‘My dad used to work on the Gas Holders so I always held a bit of a fascination for them,’ says Chivers. He was prompted into action after reading an article in a newspaper about their imminent demolition.

He adds: ‘I love industrial architecture and find the gas holders with their lattice steel frames visually really interesting. The fact that the structures were a massive part of the UK skyline for years and had become landmarks for people was also intriguing’.

The exhibition also featured a specially-commissioned sound piece by acclaimed music maker and DJ Solomon Onyemere.